ISIS has claimed responsibility for a pair of rare terrorist attacks in Iran’s capital Tehran, which some of the country’s most hard-line officials in turn blamed on the United States and Saudi Arabia. The dramatic incidents have added another layer of complexity on top of an already rapidly growing political crisis, centered on an attempt by the Saudis and their allies to isolate Qatar, which now involves the Russians and threatens to engulf the entire Middle East.

On June 7, 2017, at least seven terrorists conducted two simultaneous attacks on the seat of Iran’s parliament, known as the Majlis, and the tomb of the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the father of the country’s Islamic Revolution. The complex operation involved small arms, suicide bombs, and possibly hostage taking. The nature of the attacks and their targets were highly symbolic.

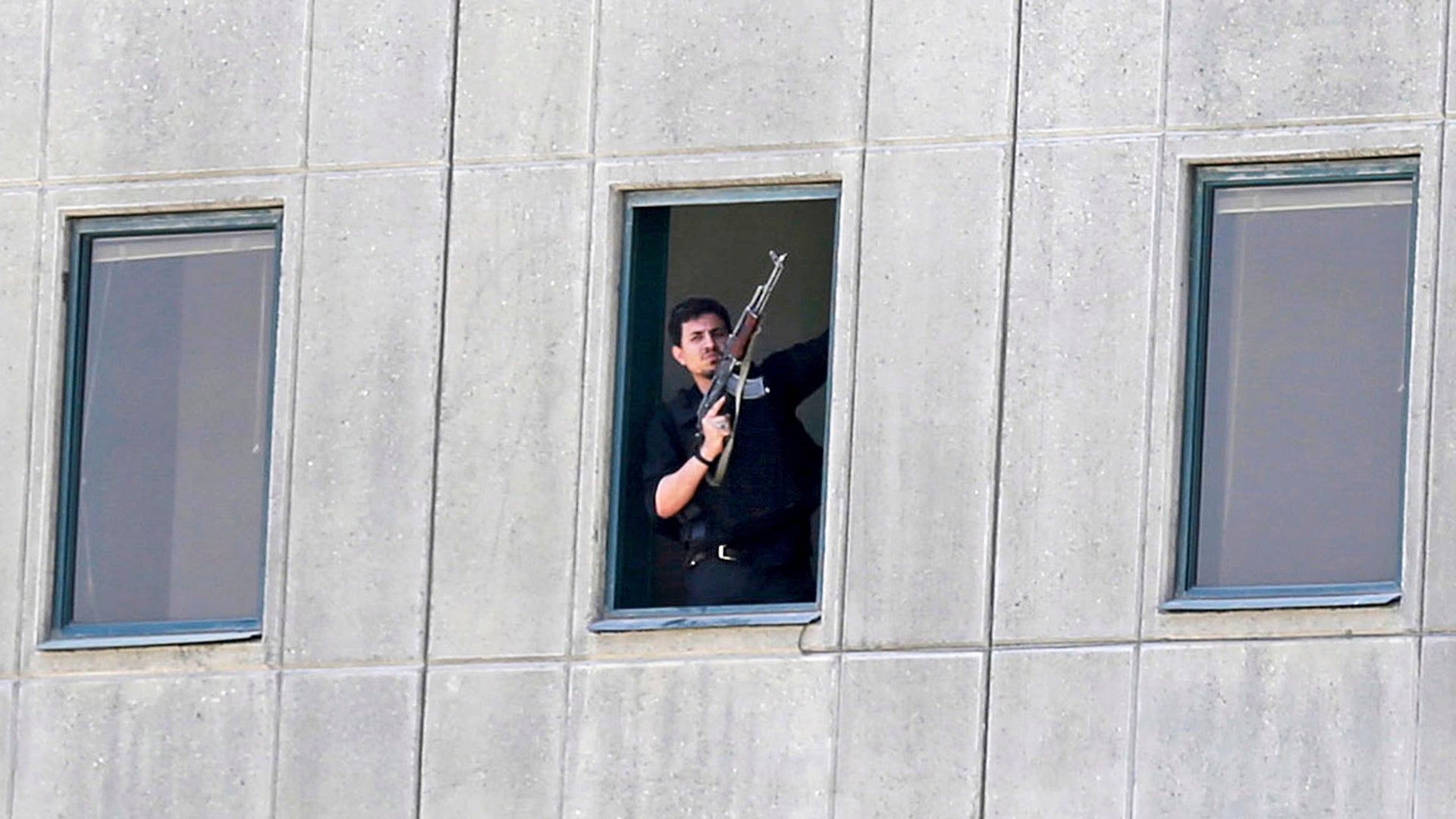

At the country’s parliament, four ISIS fighters, reportedly dressed as women, burst into an administrative building and began shooting, killing seven or eight individuals outright. Iranian state television said the Majlis was in session and another terrorist with a suicide vest made an attempt to get into the main hall before blowing themselves up, according to The Associated Press.

In total, the terrorists murdered 13 people. At the same time, additional fighters assault Khomeini’s mausoleum, with one setting off their suicide bomb in the process. Government security forces shot and killed six of the attackers and arrested a seventh, who was actually a woman. They claimed to have thwarted a third attack entirely. Reactions from Iranian government officials were swift, focusing mainly on applauding the indomitable spirit of the country, its people, and the Islamic Revolution.

“These fireworks that happened today will have no impact on the people’s resolve,” the country’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei, said afterwards “They are too weak to affect the will of the Iranian nation and that of the officials.” “The Iranian nation…will prove once again that it will crush any plot or scheme by ill-wishers through unity and solidarity and its powerful security structure,” recently re-elected President Hassan Rouhani, seen as a moderate reformist in the context of Iranian politics, assured the nation.

The Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) had a very different take. In a statement, the powerful paramilitary entity, which is nominally part of the country’s armed forces and acts as the defender of the country’s unique political system, drew a direct line between the ISIS attack and U.S. President Donald Trump’s visit to Saudi Arabia in May 2017. Rather than refer to it by name, the IRGC only noted collusion between Trump and “the rulers of a regional reactionary regime.” Iran’s hardliners often do not name countries they see as hostile, preferring to use epithets, such as “Great Satan” for the United States and “Little Satan” for Israel.

It’s worth noting that the idea of U.S.-Saudi-ISIS cabal is already a well established conspiracy theory. However, ISIS, a Sunni Islamic terrorist group, has a perfectly understandable grievance with predominantly Shia Iran over the country’s support for the regime of Syrian president Bashar Al Assad, which includes funding and providing various equipment for Syria’s own forces and various Shia militias, as well as Iraq’s majority Shia government. Since at least March 2017, ISIS has stepped up propaganda calling for attacks on Shi’ite Iranians and the state itself.

But this response is hardly surprising, given that Trump and Saudi King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud both pointedly criticized Iran during the state visit, slamming the country as a destabilizing force in the region and sponsoring terrorism – and there is significant evidence to support both claims. However, officials in Tehran see their counterparts in Riyadh as the true bad actors in the greater Middle East, funding extremists themselves – accusations that are also not easy to deny.

There is a long history of competition between the two countries and it has been increasingly, if not necessarily accurately, become framed in the context of a divide within the global Muslim community. Saudi Arabia is home to Islam’s two holiest sites and its monarchy effectively claims to be guardian of the faith worldwide, despite belonging to a relatively small branch of Sunni Islam known as Wahhabism. As such, Riyadh is actively opposed to other brands of political Islam, even among fellow Sunnis, with particular anger reserved for the Egypt-centered Muslim Brotherhood.

On the other hand, Iran’s Islamic authorities see themselves as the center of a so-called “Shia Crescent,” despite again not necessarily speaking for all of Shi’ism and its own many sects and offshoots. Iranian state media routinely brands Sunni militant groups with the term takfiri. Though this formally refers to a Muslim who has accused another Muslim of apostasy – the act of renouncing one’s religion – it has taken on a derogatory definition as someone who wrongly claims to practice the only legitimate interpretation of the faith.

As such, this latest rhetoric might not have even merited a mention had it not been for its place alongside an increasingly serious situation sweeping across the Middle East as a whole. Saudi Arabia touched off this political crisis when it decided to sever relations with Qatar. Despite being another Sunni Arab monarchy, the House of Saud has long seen the House of Thani as potentially dangerous outlier. Most galling to the Saudis, Qatar maintains relatively warm relations with Iran and offers neutral ground to operate in for even the most extreme Sunni political groups, such as Hamas and the Taliban.

Perhaps even worse for Saudi royals, the country has a vibrant and relatively free press, centered on the Al Jazeera television network, which routinely takes Arab rulers to task over poor human rights records and other abuses. The outlet has been particularly critical of the Saudi-led intervention into Yemen’s already brutal civil war, which was prompted by the rise of Houthi rebels with links to Iran. Saudi air strikes in particular have resulted in significant numbers of civilian deaths and there is evidence of war crimes and crimes against humanity on all sides.

The matter came to a head in May 2017, after reports that Qatar’s Emir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani had criticized Trump and Salman’s attacks on Iran and called for increased Arab cooperation with the government in Tehran. This came straight from Qatari state media, which later claimed hackers had broken into its website and Twitter account and planted the fake news to stir up trouble. The plan apparently worked.

On June 5, 2017, Saudi Arabia, with what appeared to be tacit approval from the Trump Administration, cut off both diplomatic and physical links with the peninsular country. Officials in Riyadh accused the government in Doha of supporting terrorism and undermining regional governments, including its own. Trump subsequently Tweeted out what seemed to be an agreement with the Saudi position. Bahrain, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates quickly followed the Saudi lead. Jordan, the Maldives, Mauritania, Morocco, and Senegal all ultimately cut ties, downgraded relations, or put new economic restrictions in place.

As we already reported at The War Zone, this had the potential to throw Qatar, as well as its neighbors and allies into chaos. Tyler Rogoway wrote:

Saudi Arabia closed its common land border with Qatar—which is Qatar’s only land border—as well as shuttering its sea and air borders with the country. The UAE and Bahrain have closed their air and sea borders with neighboring Qatar as well, and far away, Egypt closed its airspace to aircraft belonging to the peninsular nation. As a result, Qatar has lost a whopping 82% of its gulf imports as a result of the punishing measures, and the country relies heavily on these imports to survive, especially those that come through Saudi Arabia. The various players involved have also recalled their citizens from Qatar, some on very tight timelines, and have kicked Qatari nationals out of their own territories.

And the situation has only become more complex and convoluted since then. While there was no claim or responsibility or other confirmation of the cyber attack on Qatar’s state broadcaster, on June 7, 2017, CNN reported that United States law enforcement officials had come to believe not only that the hack was realm but that the intruders were Russian. As it has done after other similar accusations, the Kremlin staunchly denied any involvement. Still, Russia has been looking to gain new influence in the Middle East and North Africa, beyond long-standing partner Syria. It has made inroads with Egypt and is cultivating ties with Libyan strongman Khalifa Haftar.

At the same time, in spite of early attempts at a diplomatic resolution, with Kuwait trying to intervene and calm the situation, Saudi Arabia has only escalated their rhetoric with a set of 10 demands to be met within 24 hours. These included cutting all relations with Iran, expelling Hamas – a Palestinian offshoot of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood – from the country and seizing its assets, as well as deporting other Muslim Brotherhood representatives and other unspecified elements hostile to the Saudi-led Gulf Cooperation Council political and economic bloc. The Hamas-specific requirements may also be linked in part to warming relations between the Saudis and Israel, who both see a common enemy in Iran.

Riyadh wants Doha to stop supporting terrorists groups and “interfering” in Egypt, too. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el Sisi took power in a coup during which the military overthrew an elected Muslim Brotherhood government. Oh, and the Saudis need a state-level apology for Al Jazeera’s “abuses” and a promise to shut down the network for good.

All of this could only be humiliating for the Qatari regime and it is unlikely to comply. What happens if it doesn’t, though, is unclear. As these new developments were appearing, Turkey announced it had authorized the deployment of troops to a new overseas base in Qatar. Though the risk of an outright conflict is low and the two countries had reportedly first started discussing this plan in January 2017, the rush to complete the deal can only be seen as a product of the existing political crisis. Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party, an Islamist political party better known by its Turkish acronym AKP, is widely seen as the country’s branch of the Muslim Brotherhood. It has spoken out in support of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood in the past.

The United States, which might otherwise be a key peacemaker, is in a complicated situation. President Trump himself has already publicly sided with Saudi outrage over what may have been false statements. At home, Trump is facing a steady barrage of criticism over his handling of investigations into Russia’s attempts to undermine the American electoral process, which he insists is “fake news.” But the vast majority of the parties directly or tangentially involved in the crisis – with the obvious exceptions of Russia, Iran and Hamas – are traditional U.S. allies. Qatar happens to host the largest American military base in the region, which has been essential in the U.S.-led fight against ISIS.

On the other hand, no one in the U.S. government would want to be perceived as being soft on Iran or terrorism, especially as American officials look to enact new sanctions on Tehran over its ballistic missile programs. The Pentagon has become increasingly in danger of getting into a more significant fight with Iranian-backed militia in southern Syria as it attempts to focus on battling ISIS, too. All this in turn could push Iran’s more moderate elected authorities to side with hardliners to more actively support Qatar, potentially driving a wedge deep between it and its historic American benefactors.

In spite of these political realities, the U.S. State Department did take a smart, apolitical line in response to the Tehran terrorist attacks. “We express our condolences to the victims and their families, and send our thoughts and prayers to the people of Iran,” Heather Nauert, the Department’s top spokesperson, said in a statement. “The depravity of terrorism has no place in a peaceful, civilized world.”

Unfortunately, if it becomes any more difficult for the parties to reign in their rhetoric and defuse the situation, platitudes like this may not be enough to prevent the crisis from boiling over into something far worse.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com